The Search For a Southern Overland Route to California

Harlan Hague

The first region known to Europeans in what is now the United States was not at the mouth of the James River nor was it on the western shore of the Bay of Cape Cod. The two-year residence in present-day New Mexico by the Spaniard, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, pre-dated Sir Walter Raleigh's attempted settlement of Roanoke Island in the 1580s by forty-five years and lasted longer.

A significant Spanish presence in New Mexico began in 1598, nine years before the founding of Jamestown. Long before English settlers began to leave their boats to cut paths beyond the fall line of the James River, trails in the Southwest between Spanish settlements in Mexico and New Mexico had been well-established and regularly used.

While settlement of New Mexico continued during the seventeenth century, the Spaniards also turned their attention westward, and eventually the lure of California attracted them, as it would Mexicans and Americans at a later date. Whether traveling from the United States, New Mexico, or Mexico, however, great expanses had to be crossed to reach the fabled land.

When the Spanish discovered that they could not adequately supply and populate their California settlements by a sea route from Mexico's western coast, they pioneered an overland route from Sonora to southern California. The year was 1774, two years before the signing of the American Declaration of Independence and fifty-two years before Jedediah Smith became the first American to enter California by an overland route. The first party of emigrants to enter California overland traveled the southern route in 1775, sixty-six years before the Bartleson-Bidwell party inaugurated the California Trail as an emigrant route.

In contrast to northern trails, the southern route was no single, well-defined path. With some exceptions, it was made up of a number of trails which generally converged at or near the Pima Indian villages on the Gila River in Arizona. From there, the trail followed the Gila downstream to its confluence with the Colorado, then westward across the southern desert to the coast.

Certainly, there was no "Gila Trail," as the term is popularly used today in western literature. The term is a misnomer, and a glance at maps that trace the paths followed by southwestern explorers reveals how little the routes touched the Gila River. California-bound travelers on the various branches of the southern route did not refer to a "Gila Trail"; the term was invented much later by historians in need of a handy reference.

The selection of "Gila Trail" to fill that need was unfortunate, however, for use of the term has generated a myth that there was a single trail to California that ran alongside the Gila River. In reality, the southern route was more complex than the myth, and while the beginnings of the more northerly trails have been discussed and rediscussed, the origins of the southern route are here for the first time explored as an integrated topic. More thorough study is deserved.

The first leg of the first overland route to California was pioneered by the Jesuit missionary, Father Eusebio Francisco Kino. Arriving in 1687 in the Pimería Alta--the name then applied to today's southern Arizona and northern Sonora--to minister to Indians on New Spain's northern frontier, Kino's spiritual devotion was matched by his zeal for discovery.

Of all the pioneers who trekked southwestern trails from the sixteenth through the nineteenth century, Kino is most deserving of the title of pathfinder. On his numerous trips throughout present-day northern Sonora and southern Arizona, he seldom had any military escort and generally traveled with only a few Indian companions who seem usually to have been servants rather than guides. It is obvious, however, that the padre often followed Indian trails and was assisted by local Indians during his journeys.

In the early years of his ministry, Kino devoted his energies to building missions and otherwise extending the influence of the church within the boundaries of present-day Sonora. But in the year 1699, while on an expedition to the Gila River, Kino was given some blue shells that changed all that. The shells were similar to some he had seen on the Pacific coast side of Baja California in 1685. He had never seen them elsewhere. Kino reasoned that the shells must have come overland from the coast. Though he never ceased his quest for souls, from that year the friar occupied himself most fervently in the search for a land route to California.

Kino saw good reason for opening a road between Sonora and California. The Manila Galleon--the trade ship which traveled annually from Mexico to the Philippine Islands and back--could be provisioned from the Pimería, and the upper frontier could participate in the trade with the Galleon. A newly-prosperous Pimería then would be able to expand its commerce with the interior of Mexico and open trade with New Mexico and perhaps even beyond to New France.

According to his own count, Kino made fourteen expeditions to prove that there was a land passage to California and, further, that Lower California was a peninsula rather than an island. Indeed, he crossed the Colorado River to the California side in the course of his explorations. Kino eventually wrote of his findings: "I discovered the land-passage . . . at the confluence of the Río Grande de Gila and the abundant waters of the Río Colorado." As to that land lying west of the Colorado River, Kino added: "I assign the name of Upper California." Kino's dream of an overland route to California lapsed with his death in 1711.

More than fifty years passed before the task was taken up by another missionary, Father Francisco Garcés, a Franciscan. Cast in Kino's mold and stationed at the southern Arizona mission of San Xavier del Bac, which Kino had founded, Garcés made five journeys during his short thirteen-year ministry in the Pimería that earned for him a reputation as one of the greatest explorers in the history of the American West.

Garcés's first two journeys were missionary ventures designed to strengthen the influence of the church as far as the Gila River, but the third expedition was more important as a step toward opening a trail to California. Convinced by the successes of his first two trips that the tribes he had visited were ready for conversion, Garcés set out in 1771 to select the best sites for new missions. He traveled from San Xavier to the Gila, then down that stream. Because the Gila was swollen by recent rains, he failed to recognize the confluence with the Colorado, so he continued downstream toward the gulf. Finally deciding that the Colorado lay westward, the padre crossed the river, still thinking he was on the Gila.

In search of the Colorado, Garcés, now on the California side of the river, made two treks into the desert. Both times, he started with Indian guides; both times, his guides deserted him. How far he penetrated on these solitary journeys is not known. On the second, he came in sight of a range of mountains and saw two passes through it, but he despaired of going on and turned back.

Though he was lost part of the time, Garcés unknowingly had pioneered a new trail from the Colorado toward the Spanish California coastal settlements. The principal significance of his third expedition was its effect on the fruition of another exploration from the Pimería Alta just three years later which would reach the California coast.

The idea for searching out an overland route to California had been a dream of Captain Juan Bautista de Anza for many years. From 1769, when he unsuccessfully sought permission to organize an expedition for that purpose, Anza tried to convince his superiors that a road could and should be opened. Garcés's reports of his expedition supported Anza's view. Eventually Father Junipéro Serra, "father" of the California mission system, spoke strongly in favor of the project. Serra's advice appears to have had considerable influence on the viceroy who shortly after gave his approval to Anza's plan.

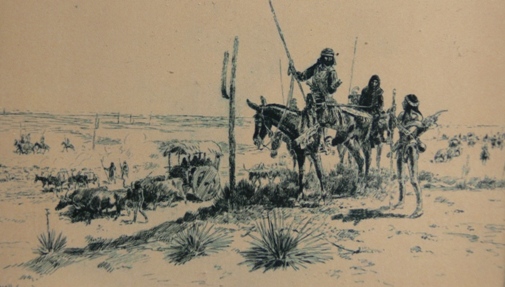

Anza's expedition departed Sonora in January 1774. To the Gila, across the Colorado, and into the desert beyond, Garcés guided the column over trails known to him. From there to the California coast, the expedition was guided by Sebastián Tarabal. Tarabal was a "mission Indian" who had run away from the California mission of San Gabriel and made his way overland to Sonora where Anza persuaded him to join the expedition.

The worst stretch of the entire trip for the Spaniards was the crossing of the Colorado Desert where both Garcés and Tarabal had been lost during their previous journeys. As a result, the Spaniards wandered and suffered until Tarabal recognized landmarks and brought the expedition to San Gabriel mission in mid-March 1774.

The first overland route to California had been found. Kino had located the trail as far as the Colorado River. Garcés extended the path across the Colorado and into the desert beyond. Anza, with the help of Garcés and Tarabal, completed the route to the Pacific Ocean.

The first practical use of the new road was made the following year. In 1775, a royal decree recognized the growing importance of Alta California and changed the seat of government from Loreto in Baja California to Monterey. Though the decree was not implemented until 1777, action was taken immediately to increase the Spanish population of Upper California. Anza was directed to lead an expedition of soldiers and colonists to establish a settlement at the Bay of San Francisco.

The expedition of 240 persons set out from Anza's frontier presidio at Tubac in October 1775. The route followed was essentially the same as the 1774 journey, except that it was straightened out in a number of places. Garcés accompanied Anza as far as the Colorado River but remained there to minister to Indians and to explore. Anza led the expedition into San Gabriel on January 4, 1776. The only death during the entire journey was a woman who died from the complications of childbirth. Indeed, the expedition's numbers had been increased by three babies born during the trip.

While Anza was proving the feasibility of travel between Sonora and California, others were attempting to directly link Spanish settlements in New Mexico and California. In early 1776, Father Garcés set out northward from the Yuma villages on the Colorado River on a journey that took him across the Mojave Desert to Mission San Gabriel, over the Tehachapi Mountains to the San Joaquin Valley, and thence back across the mountains and desert to the Colorado River. He had planned to travel directly between the Colorado and the San Luis Obispo mission on California's coast, but he had been thwarted on both the outward and return journeys.

From the Colorado, the padre satisfied a long-held desire to visit the Hopis in the plateau country of northeastern Arizona. For generations the Hopis had resisted Spanish overlordship, and they gave Garcés a cold, almost threatening, reception. The padre had hoped to fulfill his ambition to travel directly from California to the Zuñi pueblo in New Mexico, but Hopi hostility reluctantly returned him to the Colorado.

Though Garcés failed to complete his intended journey, he nevertheless had proven the practicability, or at least the possibility, of travel between Santa Fé and the Northern California settlements. In California, he had reached a point only a few days' easy march from San Luis Obispo and Monterey. He had personally traveled from the California Central Valley all the way to Oraibi, the principal town of the Hopis. Spaniards had visited Oraibi from Zuñi, and Spanish movement between Zuñi and Santa Fé was commonplace.

Also in 1776, two New Mexico Franciscans tried to locate a northern route directly from Santa Fé to Monterey in California. Though the official head of the expedition was Father Atanasio Domínguez, the Superior of the New Mexico Franciscans, it appears that Father Silvestre Vélez de Escalante, the missionary at Zuñi, was instrumental in the genesis of the project. At least it was Escalante who kept the journal of the expedition, and, whether justified or not, it is the diarist that history usually remembers.

The Domínguez-Escalante expedition failed to find a trail to California. The party traveled from Santa Fé into western Colorado, then into Utah. At a camp in western Utah, Escalante and Domínguez decided to give up and return to New Mexico. It was early October, the weather had turned colder, and they already had experienced a heavy snowfall. The mountains all around them were covered with snow, and they had failed to find a pass through the rugged San Fran- cisco Mountains, a route which Escalante thought the best to Monterey. A number of the expedition's members nevertheless disagreed with their leaders' decision and wished to continue toward California.

At this point, the party might yet have earned the distinction of being the first to reach California by a direct route from New Mexico. Or it might have earned the questionable honor of being the first party of white people to die in the snows of the Sierra Nevada. To decide the issue, the two sides agreed to "inquire anew the will of God" by casting lots. The dissenters, noted Escalante, "with fervent devotion . . . said the third part of the Rosary and other petitions, while we said the penitential Psalms, and the litanies and other prayers which follow them." That done, the lots were cast, and the leaders won the toss. Escalante thanked God, the dissenters accepted the result, and the expedition returned to New Mexico.

For the remainder of the period of Spanish sovereignty in Mexico, no further advance was made in development of the trails to California. Two mission-pueblos were established on the Colorado River among the Yuma Indians, the purpose being both to minister to the Indians and to strengthen Spain's hold on this strategic point on the overland trail. Though the Yumas had long asked for missionaries to live among them, they had not asked for Spanish settlers or soldiers. The Yumas soon became exasperated at the offenses of the latter and revolted in 1781. In three days, the Spanish presence on the Colorado vanished, and the Sonora-California road was closed.

Lieutenant Colonel Don Pedro Fages the same year led a somewhat successful punitive expedition against the Yumas, but it had no effect on re-opening the trail. Fages passed through Yuma lands again in 1782 en route to Califomia to deliver messages to the governor, but he made no attempt to re-establish Spain's hold on the region.

At the opening of the nineteenth century, Spanish control in the upper frontier was approaching an end. The Colorado- Gila region by this time had been abandoned. New Mexico continued to exist, but while the Mexican war for independence raged intermittently in the south, it existed more as an autonomous region than as a province of New Spain. As the Spanish military presence in the north declined, Indian depredations grew, and the towns of New Mexico became islands from which settlers rarely ventured far. For about 275 years, Spanish explorers had trekked the upper frontier; by the second decade of the nineteenth century, few of their trails were visible or safe.

Following the successful revolution against Spanish rule and the establishment of the Mexican state in 1821, attention was directed once again to the northern frontier regions. The security of California was seen by the new republic as its most urgent problem. Russia increasingly appeared to pose a threat to California, and trappers of the English Hudson's Bay Company pushed southward ever deeper into Mexico's territory. When it was decided that California's future as a Mexican possession required strengthening their presence there, the immediate opening of an overland route between California and Mexico became necessary.

The first concrete step in re-establishing a California-Sonora road was motivated by a need for a mail route. In 1823, Father Feliz Caballero traveled from his missions in Baja California to Sonora via the region near the mouth of the Colorado and the Gila River. The same year, Captain José Romero, commandant of the Tucson presidio, returned to Baja California over roughly the same route, but not before being robbed by Indians near the mouth of the Colorado. His later investigations into the feasibility of a trail that would pass through San Bernardino and San Gorgonio Pass and strike the Colorado north of the junction with the Gila were no more encouraging.

When Romero returned to Sonora in late 1825, Romualdo Pacheco, an engineer, accompanied the expedition as far as the Colorado river, then marched back to the coast by way of the southern, or Yuma, route. This last, the San Diego-Yuma route via Warner's Pass, eventually was recognized as the official California segment of the California-Sonora road. Although the route was dangerous, it did in fact become a road of sorts as private persons began to use it in travelling from Sonora.

While the California-Sonora trail was becoming a road, the elusive direct route from new Mexico to California again was sought. Where Garcés and the Escalante-Domínguez party had pioneered paths, Antonio Armijo's journey from New Mexico to California in 1829-1830 on a trail that lay north of the Grand Canyon was the first significant step in the development of the route that later became known as the Old Spanish Trail. A larger portion of the credit for opening the trail must go to William Wolfskill, the American mountain man who led an expedition that included George C. Yount from New Mexico via the Great Basin to California in 1830-1831; the Old Spanish Trail would follow Wolfskill's route more closely than that of Armijo.

The Old Spanish Trail was more of a "central route" than a southern one, but until the opening of shorter routes from New Mexico to California in the early stages of the war between Mexico and the United States in the mid-1840s, the trail, used more for trade than emigration, was the most heavily traveled route between the two provinces. Its principal virtue was that it lay north of hostile Indian territory. But travel over the trail was slow, and it would lose out after 1848 to the more southerly routes because gold-seekers were willing to brave both deserts and hostile Indians to speed their journeys to California.

The remaining variations of the southern route to California were established by Americans. American mountain men who came to northern Mexico after the new republic opened its borders in 1821 spread throughout New Mexico, trapping and becoming familiar with virtually every stream.

Most of their expeditions were round-trips from Santa Fé or Taos. In the fall of 1826, two parties from Santa Fé, including such notables as James Ohio Pattie, Ewing Young, George C. Yount, Michel Robidoux, Milton Sublette, and Thomas "Peg-leg" Smith, traveled to the Gila River by way of the Santa Rita copper mines in southwestern New Mexico. Eventually merging, the combined party worked down the Gila to its confluence with the Colorado to become the first Americans to do so. Then they turned north and eventually returned to Santa Fé.

Some expeditions traveled all the way to California. The first group of trappers to reach California from New Mexico was led by Richard Campbell in 1827. Unfortunately, the party's route is not known. The same year, another expedition reached the Gila River via the Santa Rita mines. The Americans trapped down the Gila. Upon reaching the Colorado, they split into two groups. One party, under George C. Yount, returned to New Mexico. The other, in- cluding James 0. Pattie and his father, Sylvester, eventually reached California in 1828 after a near-fatal walk through the desert of northern Baja California.

The next year, 1829, Ewing Young led a party of some forty trappers from Taos, bound for the Colorado. Kit Carson was a member of the group. At the headwaters of the Río Verde in northern Arizona, Young divided his party. One group returned to Taos. The other, led by Young and including Carson, headed toward California. They traveled south of the Grand Canyon, crossed the Colorado, then probably followed the dry bed of the Mojave River and crossed the mountains at Cajón Pass to arrive at San Gabriel mission in early 1830. Later, Young returned to New Mexico via the Gila River and the Santa Rita mines, arriving there in early 1831.

Other California-bound expeditions were in the field during Young's journey. It seems that a party including Peg-leg Smith from the Great Basin arrived in Los Angeles early in 1830. The expeditions of Antonio Armijo and William Wolfskill, both of which were important in establishing the Old Spanish Trail, were also out at this time.

The partnership of David E. Jackson, David Waldo, and Ewing Young sent two expeditions to California in 1831. The first, a mule-buying venture under Jackson and including J. J. Warner, traveled via the copper mines to the abandoned mission of San Xavier del Bac and the presidio of Tucson, thence to the Gila at the Pima villages, and down that stream to the Colorado.

Crossing the Colorado just below the mouth of the Gila, the party traversed the desert and passed San Luis Rey mission on the road to San Diego. If, as it seems, they passed through the San José Valley, Warner got his first glimpse of the valley where he would later build his ranch, a mountain oasis on the trail between the Colorado and the ocean.

Meanwhile, the partnership's second expedition got underway in October, 1831. Under Ewing Young, the party of around thirty-seven men included Moses Carson (Kit's brother), Benjamin Day, Isaac Williams of Rancho del Chino fame, Sidney Cooper, and Job F. Dye. Traveling a different route from that of the first group, Young led his party to Zuñi, thence to the Salt River, the Gila, and the Colorado. There, for some unexplained reason, all of the expedition's members except thirteen under Young decided to return to New Mexico. Young led the smaller group into Los Angeles in March, 1832. Later that year, Jackson returned to New Mexico with a herd of mules and horses while Young remained in California, eventually to settle in Oregon.

The last significant expedition traveling from New Mexico to California before the opening of the Mexican War left Santa Fé in 1841. A group of Americans, including Benjamin David Wilson, John Rowland, and William Workman, had decided that it was no longer safe for them to remain in New Mexico. Governor Armijo, it seems, was trying to implicate certain Americans residing in Santa Fé with the unsuccessful conquest of New Mexico by an expedition from Texas.

Little is known of the route taken by the Americans on their journey to California, only that they arrived in Los Angeles in November 1841. The party narrowly missed the distinction of being the first party of American emigrants to enter California by an overland route. Just days before, in October, the Bartleson-Bidwell party had arrived over the more northerly California Trail.

The United States Army expeditions across New Mexico to California in the opening stages of the Mexican War are better known than the earlier journeys of Americans through the Southwest. After the bloodless subjugation of New Mexico, General Stephen Watts Kearny led an advance column of the Army of the West toward California to take part in the conquest of that long-coveted province.

Departing from Santa Fé in September 1846, the column marched down the Río Grande, turning west to pass the copper mines, thence to the Gila, down the Gila, and across the Colorado about ten miles below the junction of the two rivers. The army, in some distress by this time, crossed the desert, passed Warner's Ranch, and finally reached San Diego in December 1846, but not before being battered by the Californians at San Pascual.

Kearny had hoped to open a wagon road between New Mexico and California and had begun his march with wagons. When he was forced to abandon them shortly after leaving the Río Grande, he assigned that task to Lieutenant-Colonel Philip St. George Cooke.

Cooke commanded the Mormon Battalion, a unit of the Army of the West, which was scheduled to follow Kearny's force. Cooke's Mormon volunteers marched out of Santa Fé In October 1846. Though Kearny had ordered him to follow the advance column's trail, Cooke was forced to leave the general's route at the point where Kearny had left the Río Grande.

Determined to take the wagons through, Cooke and the Mormon Battalion pioneered a road into southwestern New Mexico near the copper mines and across the continental divide in the vicinity of Guadalupe Pass. Striking the San Pedro River, the battalion turned northward along its course, left it to march westward to Tucson, thence northward again to the Gila. From that point, Cooke followed Kearny's trail to San Diego, arriving there in late January 1847.

Neither Kearny nor Cooke had plunged blindly into unknown southwestern wilds. General Kearny had recognized early in his plans for the conquest that American trappers could make an invaluable contribution to the struggle. Among a number of mountain men, some unnamed, who accompanied Kearny's force as guides and interpreters were Kit Carson, Thomas "Broken Hand" Fitzpatrick, and Antoine Robidoux. Guiding the Mormon Battalion were Antoine Leroux, Pauline (Powell) Weaver, and Jean Baptiste Charbonneau. Most had trapped New Mexico streams.

Cooke's route was shortly improved. In 1848, following the end of the war with Mexico, Major Lawrence P. Graham led a battalion of United States Army dragoons from Chihuahua to California. Marching through Janos, Graham struck Cooke's road. Beyond the continental divide, however, Graham left Cooke's route at the San Pedro River and continued westward to the Santa Cruz river before turning north to rejoin Cooke's road to Tucson. In later years, argonauts and emigrants arrived at Janos from many directions, but most of them then followed Graham's route to California, that is, Cooke's road as modified by Graham's detour to the Santa Cruz river.

Cooke and Graham may share the credit for establishing the route, but it is worth noting that Father Garcés thought of it first. Graham's trail all the way from Chihuahua to the Colorado is precisely the route suggested by Garcés in I777 for the purpose of supplying proposed missions on the Gila and Colorado Rivers.

This story of the origins of the southern route is seriously incomplete without consideration of the role played by Native Americans in the discovery and pathfinding. Historians long ago stopped writing that Spanish, Mexican or American explorers were "first to see. . ." or "first to cross. . .," thereby acknowledging that a great number of Indians had seen first and crossed first. But because of the absence of written records, Indians have received little or no credit for feats of exploration or discovery.

Most white explorers in what is now the United States Southwest were not pathfinders. Ample evidence indicates that Indians traded rather extensively between New Mexico, the interior of Mexico, and California long before the appearance of Europeans in Mexico. Spaniards, Mexicans, and Americans who ventured into these lands almost always found local Indians who were willing to point out trails that they knew and traveled often.

Most white explorers in the Southwest depended upon Indian guides. When they did not, their diaries show that they often got lost. Garcés, for example, one of the ablest of explorers, was a master at finding guides who would escort him through their own lands. On at least one occasion, when his native guides refused to go in a direction in which he insisted, Garcés relented and followed them along a path they knew. On two other occasions, when he refused to follow the advice of his guides, he got lost. Even mountain men sometimes found it expedient to employ Indian guides.

While the stories of attacks by Apaches on travelers in 1849 and after are well known, the literature of the Southwest also is full of evidence of friendly contacts between whites and Indians. From Kino through Cooke, the Pimas in their villages along the Gila River welcomed white explorers. Garcés and his Mojave companions of the trail grieved at their last parting. Kino, Garcés, and Anza alike were impressed with the eagerness of the Yumas to associate with the Spanish. Surely no other people in history have ever sought so earnestly to adopt an alien culture as the Yumas sought to place themselves under the sovereignty of the Spanish crown and Church. The Yumas were not the only Indian people so inclined. Most tribes in the Pimería Alta sought to enter the Spanish fold in some fashion.

Even the Apaches, scourge of the Spaniards and Mexicans, were largely friendly to Americans in earliest contacts. Mountain men found that Apaches hated and preyed upon Mexicans but had respect, if not admiration, for Americans. Kearny and Cooke also benefited from this sentiment. They employed Apache guides and traded with them for mules and provisions. Cordiality vanished, however, when the United States declared its sovereignty over Apachería and tried to manage the Apaches of Arizona and New Mexico.

The development of the southern route to California--as if all had been in anticipation of the gold discovery in 1848-- extended over a period of over 150 years, if its origins are traced back only as far as Kino's day. Spanish use of the trail was never heavy. The population of New Spain's northern provinces was too sparse, the financial support by the crown too uncertain, and the Indian problems too complex. Though the Mexicans re-opened the Sonora-California trail that had been closed at the end of the Spanish era, traffic was never extensive until the discovery of gold. Sonorans were among the earliest arrivals at the California mines.

The Old Spanish Trail between new Mexico and California, on the other hand, was regularly used, primarily for commerce, until it lost out to the more southerly trails. In the exodus to California after 1848, the most heavily-traveled branch of the southern route was Cooke's wagon road, including Graham's detour.

Transportation improved rapidly in the Southwest as the rush to California accelerated and the newly-acquired southwestern region began to attract American settlers. Cooke's route was improved, and new roads were opened. Stagecoach travel was inaugurated, and railroads soon entered the Southwest. A rail line spanning the region finally brought the long haul by wagon over the old trails to an end. But the centuries-old lure of California remained, and travel over the southern route continued to expand.

This article was published in the California Historical Quarterly (Summer 1976).

The author will be happy to respond to email queries. For more comment on his writing, including history, biography, fiction, screenplays and travel, click here.